I can be quite passionate about image codecs. A “codec battle” is brewing, and I’m not the only one to have opinions about that. Obviously, as the chair of the JPEG XL ad hoc group in the JPEG Committee, I’m firmly in the camp of the codec I’ve been working on for years. Here in this post, however, I’ll strive to be fair and neutral.

The objective is clear: dethroning JPEG, the wise old Grandmaster of Image Compression who ruled supreme during the first 25 years of the existence of the <img> tag and, therefore, of images on the web. As superb a codec as JPEG was, it’s now hitting its limits. Why? The lack of alpha transparency support alone is annoying enough, let alone the 8-bit limit (so no HDR) and the relatively weak compression compared to the current state of the art. Clearly, the time is ripe for a regime change.

Six combatants have entered the playing field so far:

- JPEG 2000 by the JPEG group, the oldest of the JPEG successors, available in Safari

- WebP by Google, available in all browsers

- HEIC by the MPEG group, based on HEVC and available in iOS

- AVIF by the Alliance for Open Media (AOM), available in Chrome and Firefox

- JPEG XL by the JPEG group, the next-generation codec

- WebP2 by Google, an experimental successor to WebP

Since WebP2 is still experimental and will be an entirely new format that’s not compatible with WebP, it’s too early for an evaluation. The other codecs are finalized, albeit in different stages of maturity: JPEG 2000 is already 20 years of age; JPEG XL is barely a month old.

Being based on HEVC, HEIC is, to put it mildly, not royalty free. Even though supported by Apple, HEIC is unlikely to become a universally supported codec that can replace JPEG.

This post, therefore, focuses on comparing the remaining new codecs—JPEG 2000, WebP, AVIF, and JPEG XL—to the Ancient Régime of JPEG and PNG.

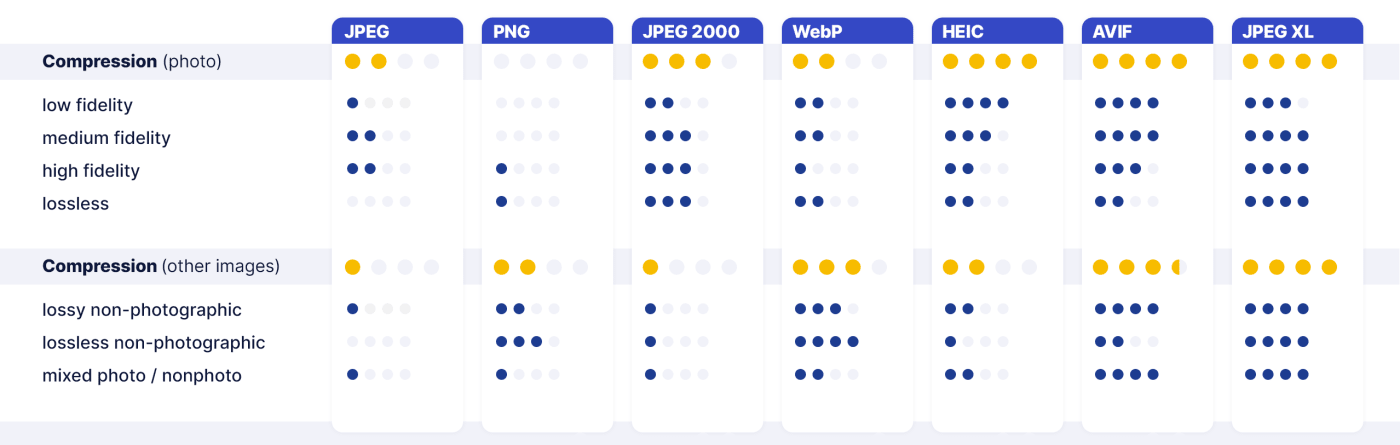

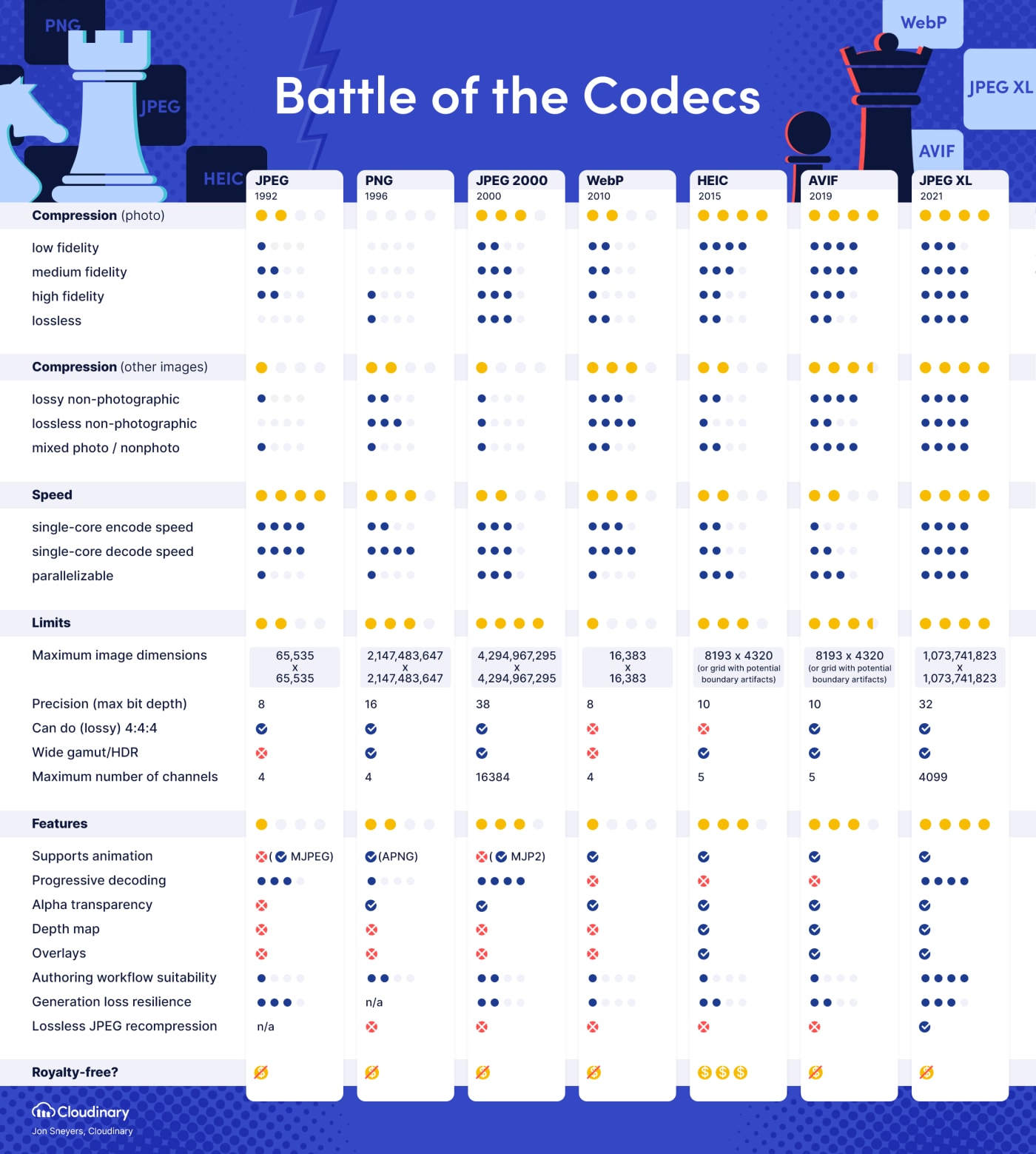

Obviously, compression is the main task of an image codec. See this scoreboard:

- JPEG was created for lossy compression of photographs; PNG, for lossless compression, which it performs best on nonphotographic images. In a way, these two codecs are complementary, and you need both for various use cases and image types.

- JPEG 2000 not only outperforms JPEG, but it can also do lossless compression. However, it lags behind PNG for nonphotographic images.

- WebP, specifically designed to replace JPEG and PNG, does indeed beat both of them in compression result, but only by a narrow margin. For high-fidelity, lossy compression, WebP sometimes performs worse than JPEG.

- HEIC and AVIF handle lossy compression of photos much more effectively than JPEG. Occasionally, they’re behind PNG at lossless compression but yield better results with lossy nonphotographic images.

- JPEG XL beats both JPEG and PNG in compression results by leaps and bounds.

When lossy compression is good enough, e.g., for web images, both AVIF and JPEG XL deliver significantly better results than the existing web codecs, including WebP. As a rule, AVIF takes the lead in low-fidelity, high-appeal compression while JPEG XL excels in medium to high fidelity. It’s unclear to what extent that’s an inherent property of the two image formats, and to what extent it’s a matter of encoder engineering focus. In any case, they’re both miles ahead of the old JPEG.

Codec Comparison at Low Fidelity

1799446 bytes PNG

1799446 bytes PNG

68303 bytes

68303 bytes

69798 bytes

69798 bytes

Decoding a full-screen JPEG or a PNG takes only minimal time, literally a blink of an eye. Newer codecs compress better but at a cost in complexity. For example, one of the main factors that limited the adoption of JPEG 2000 at its launch was its prohibitive computational complexity.

If your main goal of image compression is to accelerate delivery, be sure to take into account the decode speed. Typically, decode speed is more important than encode speed since, in many use cases, you encode only once and can do that offline on a beefy machine. In contrast, decoding is done many times, on various devices, including low-end ones.

Since CPU speed is staying stagnant in terms of single-core performance, parallelization is increasingly important. After all, the evolution trend for hardware is to have more CPU cores, not higher clock speeds. Designed before multicore processors became a reality, older codecs like JPEG and PNG are inherently sequential, that is, multiple cores yield no benefits for single-image decoding. In that respect, JPEG 2000, HEIC, AVIF, and JPEG XL are more future proof.

A key downside of JPEG—at least, the de facto JPEG—and WebP is that they are limited to 8-bit color precision. That precision suffices for images with a standard dynamic-range (SDR) and a limited color-gamut like sRGB. For high dynamic-range (HDR) and wide-gamut images, more precision is required.

For now, 10-bit precision is good enough for image delivery, and all the other codecs do support 10-bit precision. However, for authoring workflows, whereby continual image transformations might still be required, a higher precision is desirable.

WebP and HEIC do not support images without chroma subsampling, which is a different kind of limit. For many photos, chroma subsampling is fine. In other cases, such as those with fine details or textures with a chromatic aspect, or colored text, WebP and HEIC images might be substandard.

Presently, the maximum dimension-limits pose no problems for web delivery. Nonetheless, for photography and image authoring, the limits of the video-codec-based formats can be prohibitive. Note that even though HEIC and AVIF allow tiling at the HEIF container level, i.e., the actual image dimensions are essentially unlimited, artifacts might appear at the tile boundaries. For example, Apple’s HEIC implementation uses independently encoded tiles of size 512x512, which means that a 1586x752 image, for example, when saved as a HEIC, is chopped up into eight smaller images, like this:

Now if you zoom in on the boundaries between those independently encoded tiles, discontinuities might become visible:

To avoid such tile-boundary artifacts, do not exceed the maximum per-tile dimension—the size of an 8K video frame—for HEICs and AVIFs.

Originally, GIF, JPEG, and PNG could represent still images only. GIF was the first to support animation in 1989 before the other codecs even existed, which is probably the only reason why it’s still in use today despite its limitations and poor compression result. All major browsers now also support animated PNG (APNG), a relatively new situation.

In most cases, you’re better off encoding animations with a video codec instead of an image codec designed for stills. HEIC and AVIF, based on HEVC and AV1 respectively, are real video codecs. Despite its support for animation, JPEG XL performs intraframe encoding only with no capabilities for motion vectors and other advanced, interframe coding tools offered by video codecs. Even for short video segments that run for just a few seconds, video codecs can compress significantly better than the so-called animated still-image codecs like GIF and APNG, or even animated WebP or JPEG XL.

A side note: it would be great if web browsers would accept in an <img> tag all the video codecs they can play in a <video> tag, the only difference being that in an <img> tag, the video is autoplayed, muted, and looped. That way, new and masterful video codecs like VP9 and AV1 would automatically work for animations, and we can finally get rid of the ancient GIF format.

Back to still images. Besides compressing RGB pictures quickly with no size or precision limits, image codecs must also offer other desirable features.

For web images—especially large, above-the-fold ones—progressive decoding is an excellent feature to have. The JPEG family of codecs is strongest in that respect.

For web images—especially large, above-the-fold ones—progressive decoding is an excellent feature to have. The JPEG family of codecs is strongest in that respect.

All new codecs support alpha transparency. The most recent ones also support depth maps, with which you can, for example, apply effects to the foreground and background.

Images with multiple layers, called overlays, can enhance web delivery. A case in point is that you can add crisp text-overlays to photos with stronger compression and less artifacts. It’s mostly useful in authoring workflows, though. Additionally, for those workflows, JPEG XL offers features like layer names, selection masks, spot-color channels, and fast lossless encoding of 16-bit integer and 16-, 24-, or 32-bit floating-point images.

In terms of resilience against generation loss, video codecs are not exactly performing with flying colors. For web delivery, that deficiency is not critical, except in cases of images becoming, for example, a meme that ends up being reencoded many times.

Finally, a unique transition feature of JPEG XL is that it can effectively recompress legacy JPEG files without generation loss.

The newest generation of image codecs—in particular AVIF and JPEG XL—are a major improvement of the old JPEG and PNG codecs. To be sure, JPEG 2000 and WebP also compress more effectively and offer more features, yet the overall gain is not significant and consistent enough to warrant fast and widespread adoption. AVIF and JPEG XL will do much better—at least that’s what I hope.

Will there be a single winner as the dominant codec in the decades ahead? If so, will it be AVIF, JPEG XL, or the upcoming WebP2? Or WebP, now that it has universal browser support? Will there be multiple winners instead, with, for example, AVIF as the preferred codec for high-appeal, low-bandwidth encoding and JPEG XL for high-fidelity encoding? Will the new codecs lose the battle, and will the old JPEG once again survive the dethroning attempt? It’s too early to answer those questions.

For now, a good strategy might be to implement several different approaches for image encoding, not only to leverage their unique strengths but also to lessen the probability of any of the approaches becoming an attack target for patent trolls. Disk space is of no concern here because, relative to the enormous storage savings they deliver, image codecs occupy only minimal space.

Furthermore, given the many factors in play, not all of them technical in nature, success of codec adoption is difficult to predict. Let’s just hope that the new codecs will win the battle, which is mostly one that’s against inertia and the “ease” of the status quo. Ultimately, unless JPEG remains a dominant force, regardless of which new codec will prevail, we’ll reap the benefits of stronger compression, higher image fidelity, and color accuracy, which translate to more captivating, faster-loading images. And that would be a win for everybody!

Meanwhile, it has been clarified that the AVIF limits listed above apply to the highest currently defined AVIF profile (the “Advanced” profile). It is also possible to use AVIF without a profile, and then the AV1 limits apply: a precision of up to 12-bit, and maximum dimensions of up to 65535x65535 (or more using grids). For HEIC, it is possible to use the container with a HEVC payload with a precision of up to 16-bit and with 4:4:4, although most hardware implementations do not support that.